Worth reading, recent Nevada state court decisions offer highly detailed analyses describing the election process while debunking Trump’s repeated election fraud claims.

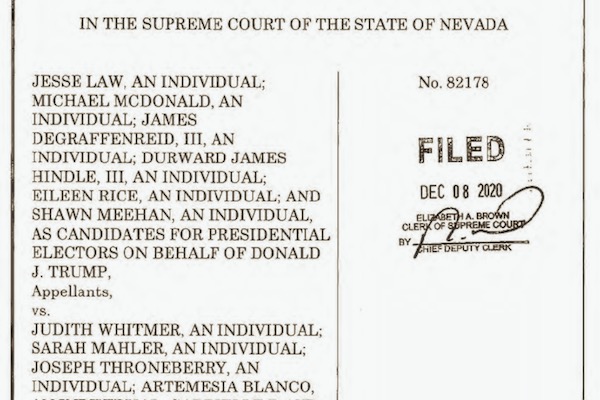

The Nevada Supreme Court has rejected President Trump’s appeal to overturn that state’s election results, affirming the lower court’s decision striking down allegations of widespread voter fraud. In yet another loss for the outgoing President (marking over 50 losses or withdrawals of post-election lawsuits), the unanimous 6-0 ruling held that the Trump team had failed to demonstrate any legal error in the district court’s decision, while noting that the district court had even considered evidence that did not meet evidentiary requirements under Nevada law for expert testimony or for admissibility.

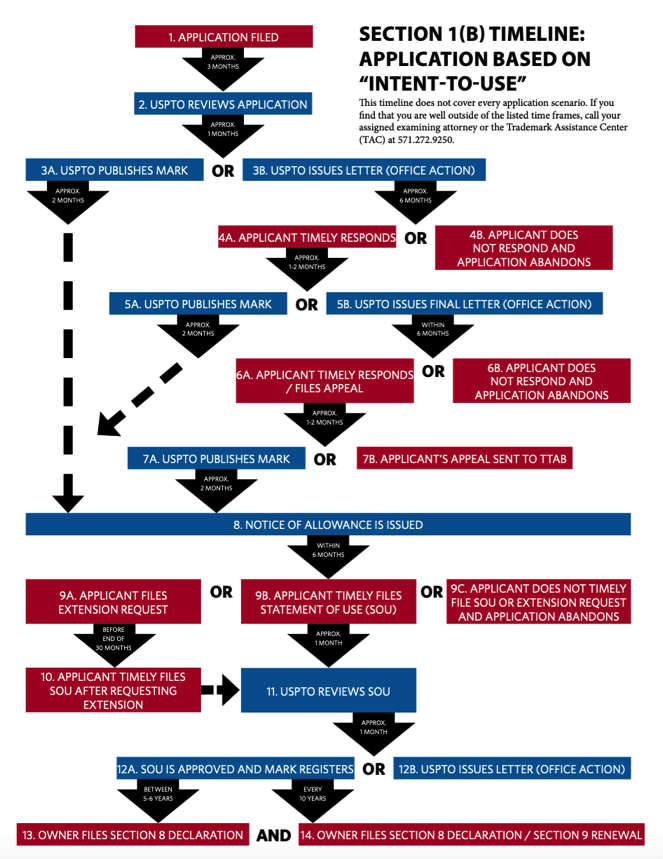

Attached to the Supreme Court’s Order, the 34 page decision (Jesse Law, et al. v. Judith Whitmer, et al., Judge James T. Russell), first described in detail the histories of, and technical workings of, the mail-in voting machines used to sort and check signatures, and the machines and software used for in-person voting. Agilis Ballot Sorting System, provided by Runbeck Election Services, with Parascript automatic signature verification technology, is the standard for mail-in voting. Dominion Voting Systems is the standard for in-person voting machines and software.

As stated by the court:

“Runbeck is a well-respected election services company headquartered in Phoenix, Arizona. It provides a suite of hardware and software products that assist with mail ballot sorting and processing, initiative petitions, voter registration, and ballot-on-demand printing. It is also one of the largest printing vendors for ballots in the United States. In 2020 alone, it printed 76 million ballots and mailed 30 million. Runbeck’s clients are state and county election officials in the United States. Runbeck does not do work for political parties or candidates.”

The Agilis ballot-sorting machine is similar to those used by the U.S. Postal Service. It takes a high res photo of each ballot as it is run through the machine, it weighs the ballot envelope, checks its barcode, and its signature, all before sorting it for counting or flagging for a deficiency. The decision details the meticulous way the hardware and software was purchased, tested, checked, audited and certified by various officials throughout the state, county and federal government. It also details the meticulous way signatures were checked, and accepted or rejected.

“If a signature was scored below 40, it was flagged for human verification. Clark County’s permanent election personnel were initially trained by a forensic signature expert and former FBI agent, and they developed a training program for temporary staff based on this instruction. During the human verification process, an election worker reviewed the signature against a reference signature on a computer screen. If the reviewer was uncertain about a signature, the signature was passed along for additional review and compared against the voter’s entire history of signatures. If uncertainty persisted, the signature was reviewed by Joseph P. Gloria, Clark County’s Registrar of Voters, as a final check. If the signature was then rejected, the voter could undertake Nevada’s statutory cure process.”

The decision also details the in-person voting process and technology provided by Dominion Voting Systems, which is really quite impressive. “These voting systems are subject to extensive testing and certification before each election and are audited after each election.” While bizarre Dominion software conspiracy theories, pushed by the likes of QAnon and former Trump team attorney Sidney Powell, have been debunked repeatedly, including by former Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) Director Christopher Krebs, this was not addressed by the court.

Examples of testing and certification cited by the court include:

- “the electronic voting systems used by Clark County were certified by the federal government when they were first brought on the market, as well as any time a hardware or software component is upgraded. This certification is done by a voting system test laboratory.”

- “The electronic voting machines are also tested and certified by the [Office of the Nevada Secretary of State], who contracts with the Nevada Gaming Control Board for this certification.”

- “Clark County’s electronic voting machines were last inspected by the Gaming Control Board in December 2019 and certified by the [Office of the Nevada Secretary of State] shortly thereafter.”

- “The voting machines are also audited against a paper trail that is generated … when voters make their selections.”

- “After each election, Clark County, like Nevada’s other counties, conducts a random audit of its voting machines. Specifically, it compares the paper trail created by the printer against the results recorded by the voting machine to ensure they match.”

- “Clark County conducted this audit following the November election and there were no discrepancies between the paper audit trail created by the printer and the data from the voting machine.”

After detailing various prior Trump election fraud cases that have been dismissed, the court waded through the evidence presented. Despite the bulk of the Trump team’s evidence consisting of inadmissible hearsay, the court still considered it. “The Court nonetheless considers the totality of the evidence provided by Contestants in reaching and ruling upon the merits of their claims.”

What follows, is the embarrassing argument set out by the Trump team, led by lawyers Shana D. Weir (Weir Law Group) and Jesse R. Binnall (Harvey & Binnall), more examples of how credible, capable lawyers refuse to touch these frivolous cases.

Incredibly, key “expert” witnesses offered by the Trump team failed miserably to abide by even the most basic requirements for offering expert evidence. Experts Michael Baselice (citing incidence of illegal voting in the 2020 General Election based on a phone survey of voters) and Jesse Kamzol (claiming significant illegal voting occurred in Nevada during the 2020 General Election, based on his analysis of various commercially available databases of voters) failed to provide sources for data, a verification of conclusions, and proof of quality control of the data presented. One expert report submitted by Scott Gessler also “lacked citations to facts and evidence” that Gessler had used to come to his conclusions and “did not include a single exhibit to support of any of his conclusions.”

The defendants, meanwhile (led by Bradley S. Schrager and team at Wolf Rifkin, Shapiro, Schulman & Rabkin, and Marc E. Elias and team at Perkins Coie), submitted the deposition testimony of Wayne Thorley, Nevada’s former Deputy Secretary of State for Elections, Jeff Ellington, President and Chief Operating Officer of Runbeck (manufacturer of the Agilis machine), and Joseph P. Gloria, the Registrar of Voters for Clark County. In each case the court found their testimony to be credible.

The defendants also produced the testimony of Dr. Michael Herron, a pre-eminent, highly qualified expert in the areas of election administration, voter fraud, survey design, and statistical analysis. As stated by the court, “Dr. Herron holds advanced degrees in statistics and political science; has published academic papers in peer-reviewed journals about election administration and voter fraud; and has an extensive record of serving as an expert on related topics in litigation before numerous courts, none of which has found that his testimony lacks credibility.”

“The Court finds there is no evidence that voter fraud rates associated with mail voting are systematically higher than voter fraud rates associated with other forms of voting.”

In analyzing the Trump team’s primary claim that voter fraud occurred at multiple points in the voting process at rates in Nevada that exceed the margin of victory in the presidential race, the court found none of the Trump team’s arguments to be persuasive. In fact, it found that Trump expert Scott Gessler actually contradicted this argument by testifying that he has no personal knowledge that any voting fraud occurred in Nevada’s 2020 General Election.

Relying on Dr. Herron’s testimony, the court concluded that:

- “After examining voter turnout in Nevada and constructing a database of voter fraud instances in the State from 2012 to 2020 … out of 5,143,652 ballots cast in general and primary elections during that timeframe (not including the 2020 General Election), the illegal vote rate totaled at most only 0.00054 percent.”

- Contestants’ allegations “strain credulity.”

- “none of the grounds [in the Contest] contains persuasive evidence [(1)] that there were fraudulent activities associated with the 2020 General Election in particular [or] the presidential election in Nevada; [(2)] that these fraudulent activities led to fraudulent votes, [or (3)] that these allegedly fraudulent votes affected the vote margin of 33,596 . . . that separates Joe Biden and Donald Trump in Nevada.”

Based on this testimony, the Court found that “there is no credible or reliable evidence that the 2020 General Election in Nevada was affected by fraud.”

Moving next to allegations and testimony submitted claiming that there were problems and irregularities with the provisional balloting process, that certain voters were allowed to vote without proper Nevada identification, and that the consequences of voting provisionally were not explained to voters, the court struck down each claim:

- “The record does not support a finding that election officials counted ballots cast by same-day registrants who only provided proof of a DMV appointment in place of a Nevada photographic identification.”

- “The record does not support a finding that any provisional voters were wrongfully disenfranchised because of directions provided by election officials or because they were not given an opportunity to cure their ballots.”

- “The record does not support a finding that voters were made to cast provisional ballots on election day and then not given the opportunity to cure their lack of identification.”

- “The record does not support a finding that same day registrants with out-of-state identification were permitted to vote a regular, rather than provisional, ballot.”

As to claims of “mismatched signatures”, namely that the Agilis machine consistently malfunctioned and accepted invalid signatures, again the court found a complete lack of credible evidence:

- “The record docs not support a finding that the Agilis machine functioned improperly and accepted signatures that should have been rejected during the signature verification process.”

- “The record does not support a finding that election workers counted ballots with improper signatures that should have been rejected.”

- “The record does not support a finding that ejection workers authenticated, processed, or counted ballots that presented problems and irregularities under pressure from election officials.”

- “The record does not support a finding that illegal ballots were cast because the signature on the ballot envelope did not match the voter’s signature.”

Nor did any of the evidence support claims that “1,000 illegal or improper votes were cast and counted” as a result of maintenance and security issues with voting machines, that 1,000 legal votes were not counted due to issues with voting machines, or that maintenance and security issues resulted in illegal votes being cast and counted or legal votes not being counted.

Echoing the baseless claims made in other Trump election fraud lawsuits, the court also rejected claims that voters were sent and cast multiple ballots and otherwise double voted, that non-Nevada residents cast ballots and those ballots were counted, and that numerous persons arrived to vote in-person on election day only to find out that a mail ballot was cast in their name already. Again, each affidavit submitted (regardless of hearsay), as in numerous other Trump election fraud lawsuits, contained conclusory, self-serving, uncorroborated accounts, that are easily explained.

While we may be tempted to cast these witnesses as liars, they may actually believe what they think they saw. They may have witnessed something they believe to be suspicious, questionable or out of the ordinary. Yet all obviously fail to ask real questions or look to other possible explanations for these supposed anomalies, most likely swayed by President Trump’s repeated mantra that there was indeed widespread, nefarious election fraud. They “Want to Believe”.

This brings to mind one witness in the Pennsylvania lawsuit, Jesse Morgan, a contract truck driver for the U.S. Postal Service. Morgan testified he delivered what he was told were ballots from a postal facility in Bethpage, New York, to Lancaster, Pennsylvania on October 21. While unsure of the amount of supposed ballots shipped (“two pallets” worth), he said he parked the USPS trailer at the Lancaster city postal facility, but when he returned the next morning, the trailer was gone. Ignoring the fact that he’s an admitted “ghost hunter” with a criminal record, Morgan may actually have believed something fraudulent took place. The problem is, he failed to ask any real questions or investigate the matter, before spreading conspiracy theories that were quickly lapped up by certain media and tweeted out by President Trump. The story was easily debunked. It actually is common for absentee ballots to be mailed from one state to another, as the ballots are meant to be used by college students, members of the military, people who travel for work, and others who may be absent on Election Day. In addition, the number of absentee ballots returned in Lancaster County was less than the number requested, which is completely normal.

Of course, responsible, ethical legal counsel, as officers of the court, are required to ask these questions and weed out frivolous claims and unsupported evidence. Here, Trump team lawyers again failed miserably to do so. Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 11 (NRCP 11 in Nevada, or NYCRR 130:1 in New York), such frivolous conduct could be sanctionable.

Certainly arguing the “Hugo Chavez, George Soros, Hillary Clinton, Dominion algorithm vote flipping” conspiracy theory would be sanctionable. But where exactly is the line? In my experience obtaining sanctions is an increasingly uphill battle. But I really do Want to Believe that at some point courts will sanction Team Trump. There certainly has been a call for censure or disbarment.

Following the Trump election fraud playbook, the usual litany of baseless allegations were also pushed by counsel in the Nevada lawsuit: that election workers were pressured to push ballots through despite deficiencies; that votes from deceased voters were improperly cast and counted; that persons cast mail ballots in other persons’ names; that election officials counted ballots that arrived after the deadline for submitting them; that Nevada failed to properly maintain its voter lists resulting in illegal votes cast and counted; and that the postal service was directed to violate USPS policy and improperly deliver ballots.

As in numerous similar lawsuits, each was rejected after careful analysis and for all of the same deficiencies.

Lastly, the Nevada district court analyzed and rejected claims that there was Biden-Harris “candidate misconduct”. Per the decision, the record does not support either “a finding that groups or individuals linked to the Biden-Harris campaign offered or gave, directly or indirectly, anything of value to manipulate votes in this election or otherwise alter the outcome of the election” or “that multiple ballots were filled out against a bus bearing the Biden-Harris emblem outside a polling place in Clark County.”

The Legal Standard

While the court held that the standard of proving fraud required clear and convincing evidence, “even if a preponderance of the evidence standard was used, the Court concludes that Contestants’ claims fail on the merits there under or under any other standard.”

In the district court’s analysis, the Trump team failed to prove:

- that there was a “malfunction of any voting device or electronic tabulator, counting device or computer in a manner sufficient to raise reasonable doubt as to the outcome of the election.”

- that “illegal or improper votes were cast and counted” and/or “legal and proper votes were not counted … in an amount that is equal to or greater than the margin between the contestant and the defendant, or otherwise in an amount sufficient to raise reasonable doubt as to the outcome of the election.”

- that “the election board or any member thereof was guilty of malfeasance.”

- that “the defendant or any person acting, either directly or indirectly, on behalf of the defendant has given, or offered to give, to any person anything of value for the purpose of manipulating or altering the outcome of the election.”

Once again, the Trump team election fraud narrative has produced no results, and released no “Kraken“, while threatening to inflict ongoing harm to America’s faith in its electoral and democratic process. Comforting, however, is the fact that America’s judicial system has proven itself to be a reliable and credible bulwark against enemies of democracy.

The district court’s well reasoned 34 page decision should be required reading for all U.S. citizens, especially those that still have doubt. It sheds light on a mountain of lies and deception, pushed by unethical lawyers led by Rudy Giuliani, Sidney Powell, Jenna Ellis, Joe diGenova, and Lin Wood, irresponsible media, unscrupulous politicians, and an outgoing, increasingly unstable POTUS.

The danger to democracy is real, as are the physical threats of violence and intimidation hurled against elected officials and their families. That recently SCOTUS unanimously declined to weigh in on the Pennsylvania lawsuit brought by Republican Rep. Mike Kelly is promising. But just how long must this go on until violence results?

“America will never be destroyed from the outside. If we falter and lose our freedoms, it will be because we destroyed ourselves.”

– Abraham Lincoln

Anthony A. LoPresti

FURTHER READING: As Trump’s hold on power fades domestic hybrid warfare rages on, via Lima Charlie News

LOPRESTI, PLLC (c) 2020 LOPRESTI, PLLC publications should not be construed as legal advice on any specific facts or circumstances. The contents are intended for general information purposes only and may not be quoted or referred to in any other publication or proceeding without the prior written consent of the Firm, to be given or withheld at our discretion. To request reprint permission for any of our publications, please contact us at info@lopresti.one. This publication is not intended to create and does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship. The views set forth herein are the personal views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Firm.