Protecting your company’s brand and trademarks should be a top priority. Failure to do so will cost you.

It goes without saying that a company’s brand identity in the marketplace is extremely important. In fact, a company’s brand, or trademark, can be its most valuable asset. What consumers associate with a brand can determine not just whether they will purchase a product or service, but also how much they are willing to pay for a product or service, how likely they are to enjoy a product or service, and whether they will recommend the product or service to others. A well-known brand’s recognition value can be worth millions. Thus, protecting a company’s brand is integral to its success. And safeguarding a company’s trademarks is integral to protecting and building its brand.

In general, a trademark is a word, phrase, symbol, or design (or a combination of those), that identifies a product or service with a particular source, e.g. your company. A trademark thus distinguishes the source of goods from others in the marketplace. Trademarks indicate both origin and quality, and they represent the goodwill from the public that a company enjoys. Since a word mark combined with a design mark often constitutes the essence of a brand, to any company trademarks are an asset to be protected.

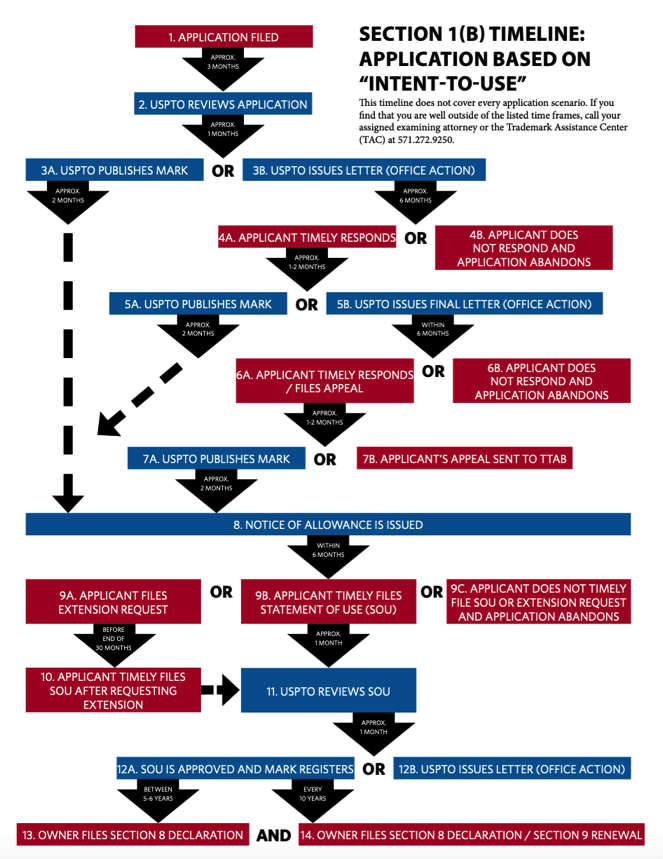

To this end, trademarks can be registered with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), either on its principal register—where distinctive marks are registered— or on its supplemental register—where inherently descriptive marks capable of acquiring distinctiveness are registered. A mark is considered distinctive if it is unlikely to confuse consumers as to the source of its respective product or service. Trademarks can also be registered at the U.S. state level, or internationally, on a country-by-country basis, or via an international trademark registration system, such as the Madrid System – subjects for a future article.

The rights afforded USPTO registrations between the principal and supplemental registers differ. Among other things, registration on the principal register provides the registrant with the legal presumption of the validity of the mark, prima facie evidence of ownership of the mark, notice to the public of a claim to ownership of the mark, the right to use the ® symbol in connection with the mark, and acknowledgment of its continuous and exclusive use. Registration on the supplemental register allows a registrant to use the ® symbol in connection with the mark, provides protection against the registration of a confusingly similar remark, and serves as a basis for registration in foreign counties. A key disparity in the registers is that on the principal register a trademark can attain incontestable status after five years of continuous use, whereas on the supplemental register there is no such possibility of achieving incontestable status.

[USPTO – “Protecting Your Trademark”]

In the U.S., the rights you may have to a trademark are not limited to those gained from registering with the USPTO. That is, you may have rights to a trademark even if the mark is not registered with the USPTO, which is not mandatory. These rights are called “common law rights” and are based on the use of a mark in commerce. Common law rights can even outweigh registration rights if the use supporting the common law rights predates that of the use supporting the registration. However, the benefits of registering with the USPTO, rather than just relying on common law rights, are many, including the ability to pursue statutory damages against an infringer.

Licensing is another key aspect to leveraging trademarks. Owning the rights to a trademark empowers a company to license its use to other parties for a profit (monetary or otherwise). When licensing agreements are drafted skillfully, they can benefit companies in a myriad of ways, such as: the collection of revenue from licensing fees, further proliferation of a mark in the marketplace with minimal effort, and exposure to new markets. However, when handled poorly, licensing a trademark could compromise the goodwill attached to it, open a company to dispute liability, or even dilute the distinctiveness of the mark. This is why it is important to seek the expertise of an attorney when licensing a trademark.

Filing Your Trademark

Unfortunately, the filing process can be met with inconsistency from USPTO examiners. Hence, knowing ways to maneuver around unfavorable decisions is integral to successfully navigating the federal trademark system. Obviously, there are too many reasons for refusal to register a mark to cover in one article, so let us focus on just one of the most common.

Refusal Based on Likelihood of Confusion

One of the most common reasons trademark applications are refused is because the examining attorney determines that there is a likelihood of confusion between the proposed mark and an existing trademark on the register. An examining attorney must refuse an application which conflicts with a registered mark, so if your proposed mark is confusingly similar to a registered mark, it could be refused. Importantly, the issue is not whether the marks themselves are likely to be confused with each other, but rather whether it is likely that consumers will be confused as to the source of the goods or services because of the marks used on them.

The tricky part about responding to an office action declaring a likelihood of confusion exists is that it is more difficult to prove the absence of something than it is to prove its presence. Thus, it can be challenging to demonstrate that two marks are unlikely to be confused. That said, it is best to focus a response to a refusal on the factors considered to determine a likelihood of confusion that were set out in In re E. I. du Pont de Nemours & Co. 476 F.2d 1357, 177 USPQ 563 (C.C.P.A. 1973). Dubbed the Du Pont factors, they are as follows:

- The similarity or dissimilarity of the marks in their entireties as to appearance, sound, connotation, and commercial impression.

- The similarity or dissimilarity and nature of the goods . . . described in an application or registration or in connection with which a prior mark is in use.

- The similarity or dissimilarity of established, likely-to-continue trade channels.

- The conditions under which and buyers to whom sales are made, i.e. “impulse” vs. careful, sophisticated purchasing.

- The fame of the prior mark.

- The number and nature of similar marks in use on similar goods.

- The nature and extent of any actual confusion.

- The length of time during and the conditions under which there has been concurrent use without evidence of actual confusion.

- The variety of goods on which a mark is or is not used.

- The market interface between the applicant and the owner of a prior mark.

- The extent to which applicant has a right to exclude others from use of its mark on its goods.

- The extent of potential confusion.

- Any other established fact probative of the effect of use.

While the weight given to each of the Du Pont factors varies case to case, the USPTO Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure states that factors 1 and 2 are “key” in any likelihood of confusion determination. So, often the best ways to respond to refusals based on likeliness of confusion are to either a) determine that the goods and services of the marks in question are not related or b) establish that the marks themselves are dissimilar—either in appearance or in commercial impression— or both.

Another way to help resolve a conflict with a registered mark is to enter into a Coexistence Agreement with the owner of the already registered mark. The parties of coexistence agreements agree that their marks are not confusingly similar to one another, and hence, pursuant to express terms, agree to use their respective marks concurrently. This agreement will likely contain a consent section, wherein the registered party gives its consent to the applying party to use and register the mark, in addition to other provisions regarding the use of marks belonging to the parties (including marks not yet in use). Alternatively, parties may enter into a simple Consent Agreement which provides consent for registration only. The USPTO considers such agreements as a factor in their determinations of likelihood of confusion.

Consent agreements must be drafted carefully to be of any use. In recent years the USPTO has been cracking down on “naked” consent agreements—agreements which contain little more than the registrant’s consent for the applicant to register their mark. Generally, naked consent agreements are not sufficient for overcoming a refusal based on likelihood of confusion.

However, the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) has clarified that significant weight should be given to consent agreements in which “competitors have clearly thought out their commercial interests”. In re American Cruise Lines, Inc., 128 USPQ2d 1157 (TTAB 2018)(internal quotations omitted). In In re American Cruise Lines the TTAB reversed a refusal to register, noting that the consent agreement at issue provided “several credible reasons [the parties] consider confusion unlikely.” Hence, consent agreements should at a minimum include such reasons.

Trademarks are an incredibly valuable asset to a business, and protecting them should be a high priority. LOPRESTI, PLLC has experience in all branding matters, and has successfully registered numerous trademarks, litigated trademark conflicts, and crafted lucrative licensing and branding agreements. The advice of an expert can make or break your efforts to protect and utilize your company’s trademarks, and hence your valuable brand. To learn more about how LOPRESTI, PLLC (lopresti.one) can make the most of your brand and trademarks, please contact us.

Article by Ashley Bogdan

LOPRESTI, PLLC (c) 2020

LOPRESTI, PLLC publications should not be construed as legal advice on any specific facts or circumstances. The contents are intended for general information purposes only and may not be quoted or referred to in any other publication or proceeding without the prior written consent of the Firm, to be given or withheld at our discretion. To request reprint permission for any of our publications, please contact us at info@lopresti.one. This publication is not intended to create and does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship. The views set forth herein are the personal views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Firm.